Frames In Flight Explained

For most of my career as a rendering engineer working with Vulkan, I’ve been confused about synchronization in CPU-GPU environments, adding to that confusion were terms like “Frames In Flight” thrown around, sometimes having different meanings for different people. In this post, I want to talk about what “Frames In Flight” means for me, how we handle it using timeline semaphores and understand how to tweak it for more complex scenarios.

Before we get started, make sure you have a clear and basic understanding of command buffers, their life-cycles, how they are submitted to queues and how seamphores signal/waits work in modern APIs such as Vulkan and D3D12.

The term “Frames In Flight” implies having “frames” we render to and possibly present; but I should mention that this idea will help with compute-only scenarios too, when done in compute loops analogous to draw/render loops.

TL;DR “FramesInFlight” is CPU telling the GPU: “You go ahead and render this frame, I’ll try to prepare the next frame for you while you’re doing that.”

Most of the code written here shows a simplified usage of Nabla API, our Open Source GPU Programming Framework, It’s built on top of Vulkan but avoids boilerplate code in API front-end.

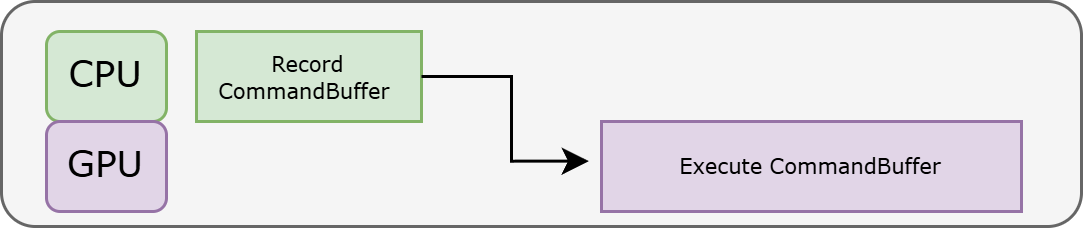

The Dumbest CPU-GPU Synchronization Possible

It helps when I start to think about the dumbest scenario possible first and move my way up from there.

Here is how each “frame”/iteration in our draw loop looks:

// 1) Record CommandBuffer for frame

cmdbuf->begin();

// record draws, dispatches, renderpasses, subpasses, barriers, or anything you can record into a command buffer

cmdbuf->end();

// 2) Submit CommandBuffer

IQueue::SSubmitInfo submitInfo =

{

.waitSemaphore = { sema, frameNumber }, // waits on value = frameNumber

.signalSemaphore = { sema, frameNumber + 1 } // signals value = frameNumber+1

.commandBuffer = cmdbuf,

};

graphicsQueue->submit(submitInfo);

// we have submitted our commands to the GPU, it will signal frameNumber+1 on our timeline semaphore when it's finished

// 3) CPU Block on value = frameNumber+1

ISemaphore::SWaitInfo submitDonePending = {

.semaphore = sema,

.value = frameNumber + 1,

};

device->blockForSemaphores(submitDonePending);

// After this, we're sure the submission has finalized and we can proceed safely on the next iteration/frame

frameNumber++;

This is dumb for two reasons:

- CPU Stalls: CPU doesn’t do anything when GPU is executing the commands.

- GPU Stalls: GPU doens’t do anything when CPU is recording the commands.

Note that .waitSemaphore = { sema, frameNumber } is not the main focus here. This is a GPU wait, ensuring that the current frame only starts execution after the previous frame has completed and released its resources.

The key point for us is the CPU-side blocking with blockForSemaphores.

If you’re new to this, you might wonder, “why even block on the CPU and wait for GPU job to finish?” or “can’t we just submit the frame and move on to the next?”, Well it’s because of a very important basic fact:

“You can’t record into a command buffer while it’s being executed on the GPU”, or as Vulkan puts it: “Whilst in the pending state, applications must not attempt to modify the command buffer in any way - as the device may be processing the commands recorded to it. “

So how can we make this better then? Let’s have more command buffers!

With more command buffers we have the opportunity to record into a command buffer, while the others are executing on the GPU.

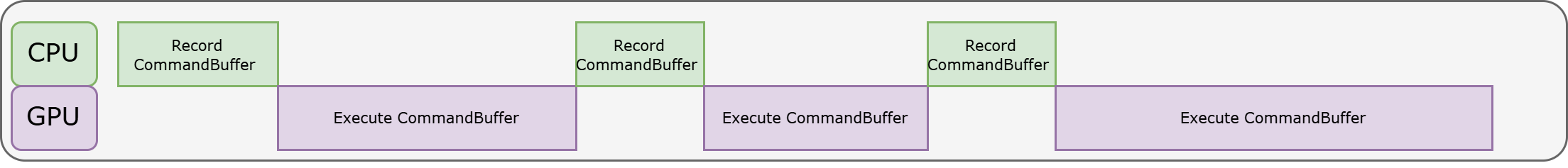

More Command Buffers!

Let’s see how it can work with 3 command buffers:

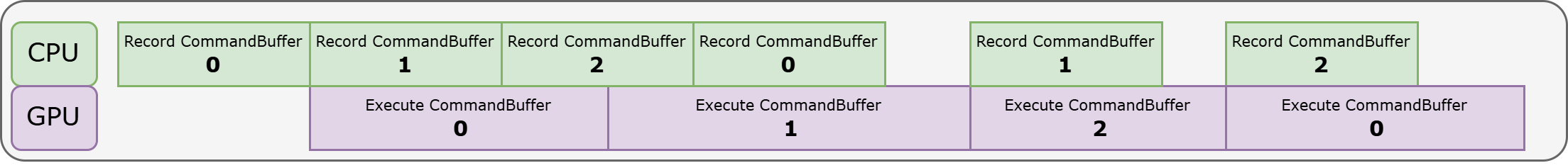

As you can see in the example figure above, CPU and GPU can have much better overlap. For example CPU is preparing command buffer 1 while GPU is executing command buffer 0.

Now let’s break down the code for this:

const uint32_t FramesInFlight = 3; // this is also the number of command buffers we have.

// 1) Selects which of the 3 command buffers to use for a given frame by cycling through the 3 command buffers based on the current frameNumber.

auto cmdbuf = commandBuffers[frameNumber%FramesInFlight];

// 2) CPU Block until command buffer is available

if (frameNumber>=FramesInFlight) // no need to wait for anything for the very first frames.

{

ISemaphore::SWaitInfo submitDonePending =

{

.semaphore = sema,

.value = (frameNumber-FramesInFlight) + 1, // commandBuffer[frameNumber%FramesInFlight] signalled this value previously and we must wait/block on it

};

device->blockForSemaphores(submitDonePending);

}

// 3) It's safe to begin this command buffer now as all previous executions have finished (we know this thanks to the blockForSemaphores above)

cmdbuf->begin();

// record draws, dispatches, renderpasses, subpasses, barriers, or anything you can record into a command buffer

cmdbuf->end();

// 4) Submit CommandBuffer

IQueue::SSubmitInfo submitInfo =

{

.waitSemaphore = { sema, frameNumber }, // waits on value = frameNumber

.signalSemaphore = { sema, frameNumber + 1 } // signals value = frameNumber+1

.commandBuffer = cmdbuf,

};

graphicsQueue->submit(submitInfo);

// we have submitted our commands to the GPU, it will signal frameNumber+1 on our timeline semaphore when it's finished

frameNumber++;

Believe it or not, this is what I mean when I say we have frames in flight. Here we have 3 command buffers so our FramesInFlight is equal to 3.

Note that we moved the semaphore blocking to the beginning of the frame, it is simpler and more intuitive at the beginning to wait until the resources and command buffers are available for re-use.

Common Misconception

When I started learning Vulkan in 2019, I used to look at Vulkan examples that followed a similar pattern (but with fences instead of timeline semaphores). Those examples were written in a way that made you think “frames in flight” means parallel execution on the GPU.

Running multiple tasks in parallel on the GPU can theoretically improve throughput by allowing more tasks to be executed simultaneously, However when talking about executing entire frames in parallel, it requires duplicates of all your dynamic frame resources to prevent Write-After-Read (WAR), Write-After-Write (WAW), and Read-After-Write (RAW) hazards.

In practice, running multiple frames in parallel on the GPU isn’t feasible for several reasons:

- VRAM limitations and the complexity of managing several copies of the same dynamic resources (broadcasting updates).

- More GPU occupancy doesn’t always mean better performance, especially with similar workloads. [4]

- it means a later frame causes an earlier frame to contend for execution resources, and the earlier frame finishes rendering later than it otherwise would have.

This is why “Frames in Flight,” for me, means CPU recording and enqueueing work for the next frames while the GPU is executing a single frame, and NOT the parallel execution of commands from different frames on the GPU.

Multiple Submits and Timeline Semaphores

In more complex scenarios in real-world applications, a single frame may include multiple submits. Some of these submits might be compute-only, graphics-only, or dependent on swapchain acquire. What do we do now?

In these situations, each of those submits in a single frame has its own set of command buffers, and we perform blockForSemaphores just before we start recording into them.

We do this before every submit to ensure that the command buffer for the submit is safe for re-use:

if (frameNumber>=MaxFramesInFlight)

{

// waits for MaxFramesInFlight submits ago and makes sure `renderCommandBuffers[frameNumber%MaxFramesInFlight]` is done executing.

const ISemaphore::SWaitInfo submitDonePending = getWaitInfoForSubmitOffset({.submitOffset = MaxFramesInFlight });

device->blockForSemaphores(submitDonePending);

}

auto renderCmdBuffer = renderCommandBuffers[frameNumber%MaxFramesInFlight];

If you have six different submits in your frame, you’ll most likely see a similar piece of code in six different places before their command buffer begins recording.

Swapchain AcquireNextImage

We mainly focused on command buffers, which is the primary limiter of how many submits/frames we can have in flight, if you have 3 command buffers then you can’t have 4 frames in flight. but this is not the only resource limiting us to have more submits or frames in flight.

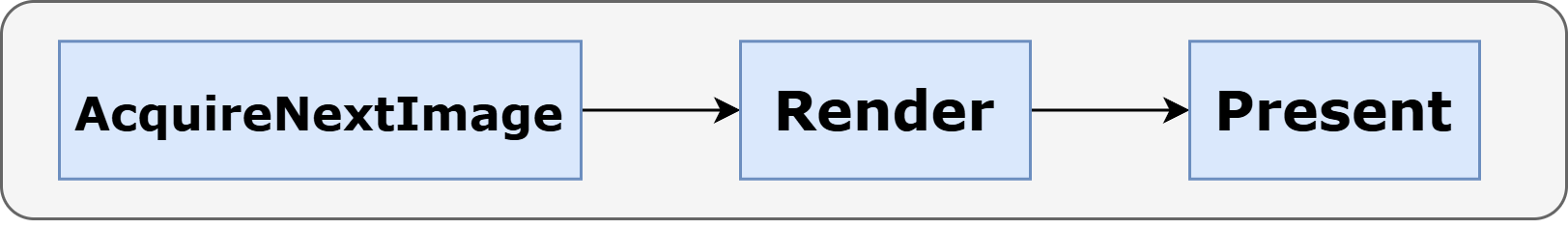

Another limitation comes up when you’re rendering to a monitor using swapchains and surfaces. If you have worked with swapchains before, you’re likely familiar with the typical “AcquireNextImage —> Render To Image —> Present Image”.

The number of images a swapchain has, is another limiter on how many frames you can have in flight, let’s break it down.

AcquireNextImage provides an index to one of the multiple images available in the swapchain, then you use that index to retrieve and render into that swapchain image and eventually Present it to the display.

This cool animation from TU Wien’s Vulkan Lecture Series visually demonstrates this pattern.

However, there’s something the visualization doesn’t show: AcquireNextImage gives you the index of the next image to use, but that doesn’t mean the image is immediately ready (depends on driver implementation). So how do you know it’s ready? This function accepts a semaphore, which it will signal once the image is ready. Waiting on that semaphore ensures the image is good to go. This semaphore is typically waited on by the GPU through the waitSemaphores parameter in the Submit.

Assume you have 3 command buffers but your swapchain has only 1 image, then a good scenario would be:

- 1 frame is executing on GPU and eventually presents

- 1 frame is pending execution waiting on Acquire of Swapchain Image after previous present is done

- 1 frame is recording it’s command buffers not submitted yet

Similar to the example, even though you only have limited number of swapchain images, you may have multiple frames waiting to execute, all waiting for the swapchain image to be available.

However, if your application is polling inputs –> recording –> submitting frames very quickly, there could be a noticeable lag between the frame being presented on the screen and the one you’re currently processing. This makes your application feel delayed, as the frame being presented corresponds to input from several steps behind. If you’re curious about why sleeping the CPU thread can sometimes help reduce this lag, check out this discussion on Graphics Programming Discord.

Video is courtesy of Timo Suoranta

This is why we recommend that FramesInFlight also take into account the number of swapchain images, as well as the number of command buffers per submit.

In Nabla, unlike Vulkan, this is not just a recommendation—there is a strict limit on how many acquires can be in flight (i.e., you cannot call AcquireNextImage before the previous ones have signaled their semaphores). The primary reason for this limitation is that Nabla emulates timeline semaphores through adaptor binary semaphores and empty submits. This is necessary because Vulkan’s AcquireNextImage can only signal binary semaphores, not timeline semaphores.

That’s why you can see this pattern in Nabla examples’ render loops:

// 1) Same as before, Selects which of the command buffers to use for a given frame by cycling through the `MaxFramesInFlight` command buffers based on the current frameNumber.

uint32_t resourceIx = frameNumber%MaxFramesInFlight

auto cmdbuf = commandBuffers[resourceIx];

// 2) Semaphore CPU Block

const uint32_t framesInFlight = core::min(MaxFramesInFlight, swapchain->getMaxAcquiresInFlight());

if (frameNumber>=framesInFlight)

{

// waits for `framesInFlight submits ago` making sure safe usage of command buffer and not calling acquire more than we should

const ISemaphore::SWaitInfo submitDonePending = getWaitInfoForSubmitOffset({.submitOffset = framesInFlight }); // Note: using framesInFlight here instead of MaxFramesInFlight

device->blockForSemaphores(submitDonePending);

}

swapchain->acquireNextImage(&outImageIndex, currentAcquireSignalSemaphore);

// Other stuff... Command Buffer Recording to draw into swapchainImages[outImageIndex] and Submitting for the frame...

Just like before, we’re indexing our resource/command buffer using MaxFramesInFlight, but we’ve introduced a new variable that’s only used for semaphore block:

const uint32_t framesInFlight = core::min(MaxFramesInFlight, swapchain->getMaxAcquiresInFlight());

Currently swapchain->getMaxAcquiresInFlight() returns imageCount+2u.

For example if your imageCount is 3, and you have 8 command buffers, the maximum number of frames in flight would be limited to 5 = min(3+2, 8) and blockForSemaphores ensures that you do not exceed this limit.

We calculate this framesInFlight dynamically at runtime within the loop as the swapchain can be recreated during execution, for instance, due to events like window resizing.

Most importantly, the swapchain tells you how many images it has after creation. You provide a minImageCount, but the swapchain can give you more images than that. The reason we don’t cache this value is because the swapchain can be recreated, and when it’s recreated, it’s not obligated to give you the same number of images as before.

Conclusion

We’ve explored how the concept of frames in flight enhances CPU-GPU work overlap, FramesInFlight can be thought of as the CPU telling the GPU: “You go ahead and render this frame, I’ll try to prepare the next frame for you while you’re doing that.” and we examined how timeline semaphores in Vulkan/Nabla are used to achieve this.

We also highlighted how factors like the number of swapchain images can impact the ability to keep multiple frames in flight.

I hope this helps anyone looking to improve CPU-GPU synchronization in their applications and I’d be more than pleased to hear feedbacks.